Audio: minor harmony (0:08)

| SCALE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melodic minor | i | ii | III+ | IV | V | vio | viio |

| Harmonic minor | i | iio | III+ | iv | V | VI | viio |

| Natural minor | i | iio | III | iv | v | VI | VII |

| Minor | i | iio | III | iv | V | VI | viio |

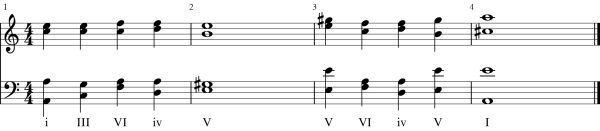

minor harmony is a wind quartet playing minor harmony in the key of A minor. The minor harmony figure shows the score. The minor harmony table lists the triads in the melodic, harmonic and natural minor scales followed by the most commonly used triads in minor harmony.

Minor harmony is a pithy term to describe the process of writing functional harmony in a minor key.

Minor harmony is more complicated to write than major harmony because not only are there three different minor scales to choose from but writers of minor harmony have not been exactly consistent in their choice of scale.

The commonly used chords in minor harmony are shown in the bottom row of the minor harmony table. They are a mixture of chords from all three of the minor scales. A lot of minor harmony writers use these chords. A lot, but not all. It is perfectly feasible to write minor harmony using a chord from any of the minor scales. For example, a minor ii from the melodic minor scale can replace the diminished iio, or a IV can be used instead of a iv, or a VII from the natural minor scale can replace the viio.

It is not uncommon to replace the minor triad i with a major triad I in a cadence at the end of a section of music, as shown in the final bar of minor harmony. This is done by sharpening the third degree of the scale, and the sharpened third is called a Picardy third.

Minor harmony nearly always sharpens the leading note of the scale. A whole tone between the leading note and the tonic is not perceived as lending an air of closure to a piece of music in minor harmony. The gap, a whole tone, is too wide, it should be a semitone, the same as in major harmony. This explains why the dominant is a V and not a v (V contains the leading note, v does not), and why the triad with the seventh degree as root is a viio and not a VII. It does not explain why the chord on the third degree is a major III triad and not an augmented triad III+ (III does not contain the leading note, III+ does). Do not look for consistency in minor harmony is the moral of the story.

Thankfully, a minor chord progression is a little easier to write than its major counterpart because the dissonant iio and viio are often avoided. This leaves five chords to play with: i, III, iv, V and VI, all of which are used in minor harmony.

A chord progression in minor harmony invariably starts with the tonic triad i and ends with either i or I with a Picardy third.

V-i is the bedrock chord progression in minor harmony for exactly the same reason as V-I is in major harmony, the root moves down by a fifth. The dominant triad is usually, but not always, a major triad V. Occasionally, the dominant minor triad v is taken from the natural minor scale and used instead. Never mind that the natural minor scale is a modal scale, the aeolian, and that functional harmony is not supposed to be modal, when needs must, any chord from any minor scale will do in minor harmony

The commonest way to link two chords in functional harmony is to move the root down a fifth. The roots in i-IV, III-VI and V-i all move by fifth down. All other root movements by fifth involve a diminished chord and are generally avoided except for the occasional iio-V. Root motion by third and by step are both perfectly acceptable. minor harmony contains all types of root motion: by repeat, by step, by third and by fifth.

To sum up how to write functional minor harmony: use any type of root motion and the triads i (sometimes I in a cadence), sometimes iio (though occasionally ii), III (sometimes III+), iv (occasionally IV), V (occasionally v), VI and, rarely, viio (with the occasional surprise VII). What could be simpler?