| # OF NOTES | HARMONY |

|---|---|

| 2+ | Drone harmony |

| Parallel harmony | |

| Counterpoint | |

| Self harmony | |

| Chordal harmony | |

| 3+ | Functional harmony |

| Pop harmony | |

| 4+ | Jazz harmony |

| 12 | Chromatic harmony |

| 12+ | Synthetic harmony |

The harmony table lists the main topics that are covered in this part of the guide.

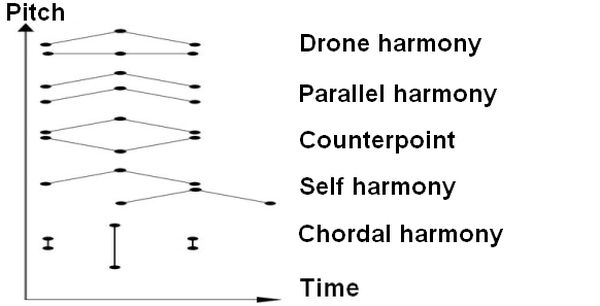

The two part harmony figure shows different approaches to two part harmony.

Harmony consists of simultaneous notes.

Harmony is two-dimensional 2D. The dimensions are pitch and time, as shown in the harmony figure. Time is the horizontal dimension, the dynamic aspect of harmony, and is concerned with the development of melodies and the progression of chords. Pitch is the vertical dimension, the static element of harmony, and is concerned with the interaction of notes at a single point in time to form chords.

Different approaches to harmony place a different emphasis on the relative importance of pitch and time. Melody-based approaches emphasise the horizontal dimension, time, whilst chord-based approaches emphasise the vertical dimension, pitch. Broadly speaking, the fewer the number of simultaneous notes, the more the melody-based approaches predominate. Add more notes into the mix and the chord-based approaches start to take over.

Polyphony is a term used to describe melody-based approaches to harmony which focus on the horizontal dimension. Polyphony is treated by some writers on the subject as distinct from harmony, with harmony focussing exclusively on the vertical dimension, the chord. The guide does not make a distinction between polyphony and harmony for two reasons. First, simultaneous melodies are not independent of each other, their notes interact, whether intentional or not. Second, it is often better to focus on both dimensions together when writing harmony. Occasionally, the emphasis will be solely on the horizontal dimension, writing multiple melodies, other times it will be solely on the vertical dimension, writing chords, much of the time, it will be on both together.

The guide tackles harmony in terms of the number of simultaneous notes that sound.

Two part harmony is the cornerstone of harmony. Or, rather, it should be. Unfortunately, it is not a well-defined subject in music, which should come as a surprise if you have never written harmony before. Information on the topic is curiously sparse, sparse to the point of nonexistence, to be honest. Most books and commentary on harmony proceed directly from melody to chords with three notes and gloss over the intervening stage. Poor old two part harmony is stuck in a twilight zone between melody heaven and chord hell. We will try to rectify the situation by writing five different approaches to harmony in two parts. Mostly in two parts but not exclusively so. When an approach can easily be extended from two parts to multiple parts we will explain why and show how. Four of the approaches are melody-based: drone harmony, parallel harmony, counterpoint and self harmony. The fifth approach is chord-based chordal harmony.

Harmony with three and more notes is illustrated in five approaches: functional harmony, pop harmony, jazz harmony, chromatic harmony and synthetic harmony. A constant theme running through these approaches is tonality: the more notes there are, the fuzzier the key becomes. Functional harmony and pop harmony are both written in a clearly identifiable key (although that key can and does change). Jazz harmony is written in a single key or in multiple keys and the key can change with each chord. Chromatic harmony uses twelve notes, synthetic harmony uses an infinite number of notes, and both dispense with the idea of key altogether.

We take time out in the middle of all this activity to mull over a hoary old chestnut in the harmony and melody section: does the melody or the harmony come first?

To start us off, we look at the distinction between part and group.